Over the span of just a century, the English bulldog has undergone a regrettable transformation due to extensive selective inbreeding. Throughout history, humans have intentionally bred dogs to exhibit certain characteristics and appearances, resulting in diverse breeds ranging from tiny to massive, round to elongated. However, the bulldog stands out as one breed that often looks a bit down in the dumps.

Unfortunately, this pursuit of aesthetics through genetic manipulation has led to unforeseen health issues lurking beneath the surface. By breeding dogs for specific traits, we have inadvertently introduced a host of health problems, such as heart conditions, liver complications, bone issues, and more, ultimately reducing their lifespans. Bulldogs, in particular, suffer from a range of health concerns including heart and hip problems, breathing difficulties, and various other maladies as a result of generations of inbreeding. Modern English Bulldogs typically have a lifespan of around six human years, or 42 dog years.

The situation for bulldogs has reached a critical point, with a 2016 study in Canine Genetics and Epidemiology suggesting that the subspecies is now beyond the possibility of genetic intervention to improve their health. The lack of genetic diversity among bulldogs is so severe that introducing new, healthy genes into the breed is unlikely to make a significant difference.

So, how did a once robust and resilient breed like the bulldog become plagued with sickness and short lifespans in modern times? Let’s take a look back at their history.

12,000 B.C.: The gray wolf

Research in the past decade has focused on the mutations that transformed gray wolves into the dogs we know today. It is believed that some wolves, inclined to be more social and less aggressive, began to approach human settlements for scraps of food. Through a process of natural selection, these friendlier traits were passed down to their offspring, eventually leading to the creation of social proto-dogs, according to Dr. Krishna Veeramah, a population geneticist at Stony Brook University.

The first confirmed dog specimen, not a wolf, dates back 14,000 years to Germany. However, there are other specimens that resemble dogs but may actually be small wolves, making it challenging to pinpoint the exact beginnings of dog domestication.

The physical changes that accompanied domestication included dogs developing the ability to digest starch and fats commonly found in human foods, allowing them to survive on agricultural scraps and meat.

A significant aspect of domestication occurred in the brain, with research indicating that domesticated dogs have altered production of neuropeptides like CALCB and NPY that impact behavior. These mutations led to differences in the prefrontal cortices of dogs compared to wolves, contributing to higher levels of cognition and social behaviors in dogs.

Overall, the evolution of dogs from wolves involved a process of fine-tuning, with the biological changes enabling them to be friendly and empathetic companions to humans.

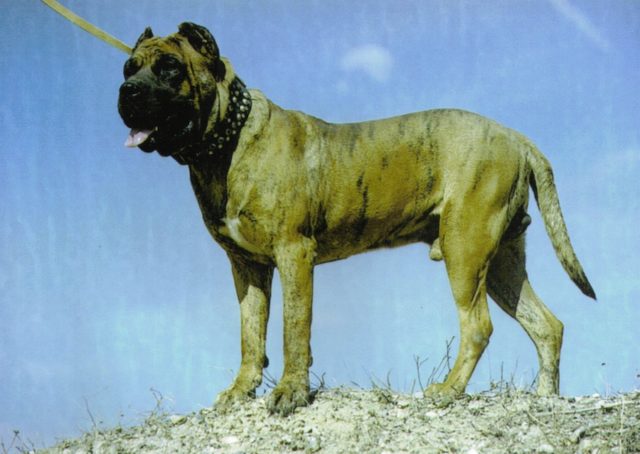

During the Middle Ages, the Alaunt and the mastiff were prominent breeds known for their strength and loyalty. These dogs were often used in battle and were valued for their protective nature. The Alaunt, believed to be a descendant of the ancient pugnaces Britanniae, played a crucial role in history as a fearless warrior alongside soldiers. Additionally, mastiffs were also highly regarded for their size and power, making them ideal guardians for homes and livestock. Today, their legacy lives on in the modern English Bulldog, a beloved breed known for its tenacity and charm.

It is a bit unclear when it comes to tracing the lineage of the modern bulldog, but it is believed that the British Alaunt could be one of its distant predecessors. Different terms have been used over the years to refer to various dog breeds, making it challenging to pinpoint the exact ancestor of the bulldog. The alaunt is thought to be a common ancestor shared by both the bulldog and the mastiff, which was originally brought from Asia. However, some argue that bulldogs may have descended directly from mastiffs. The term “mastiff” was once used broadly to describe large dogs, adding to the confusion surrounding the bulldog’s early origins.

In the 1890s, an illustration was created showing the practice of bull baiting, where dogs were pitted against bulls with varying degrees of success. The image, credited to Samuel Henry Alkin, is now in the Public Domain.

Tibetan Mastiffs, originally from Tibet and descended from Chinese dogs, have genetic mutations that enabled them to survive in high altitudes, as revealed in a genetics study published in 2014 in Molecular Biology and Evolution. Some of these genetic changes are similar to those found in humans who have also adapted to living in such extreme conditions.

During the 13th century in England, mastiffs were commonly used in staged bull baiting events, where dogs would attempt to subdue an enraged bull by gripping its nose with their teeth and trying to bring it down. The bulls, on the other hand, would protect themselves by keeping their heads low and tossing the dogs into the air with their horns.

In the Renaissance era, breeds like the Dogo de Burgos and Bulldogg were prominent in these events, showcasing the historic use of mastiffs in these violent and dangerous spectacles.

In 1900, an Englishman named John Proctor made an interesting discovery when he bought a plaque from a French Bulldog breeder, A. Provendier. The plaque, dating back to 1625, depicted a Burgos Mastiff labeled as “Dogo de Burgos.” Interestingly, at that time, the Burgos Mastiff looked very similar to a modern bulldog.

A letter sent from Spain to London in 1631 requested the shipment of a “good Mastive dog” along with some “good bulldoggs.” These requests mark the first instances in written history where bulldogs and mastiffs were differentiated as distinct breeds.

In Johannes Caius’ 1576 book “Of English Dogs,” the mastive or bandogge were still considered the same breed and described as large, stubborn, loyal dogs used for bull-baiting. It was only after this time that the bulldog and mastiff were recognized as separate breeds.

Fast forward to the 1800s, and the Bulldog breed was becoming more defined and recognizable in its own right.

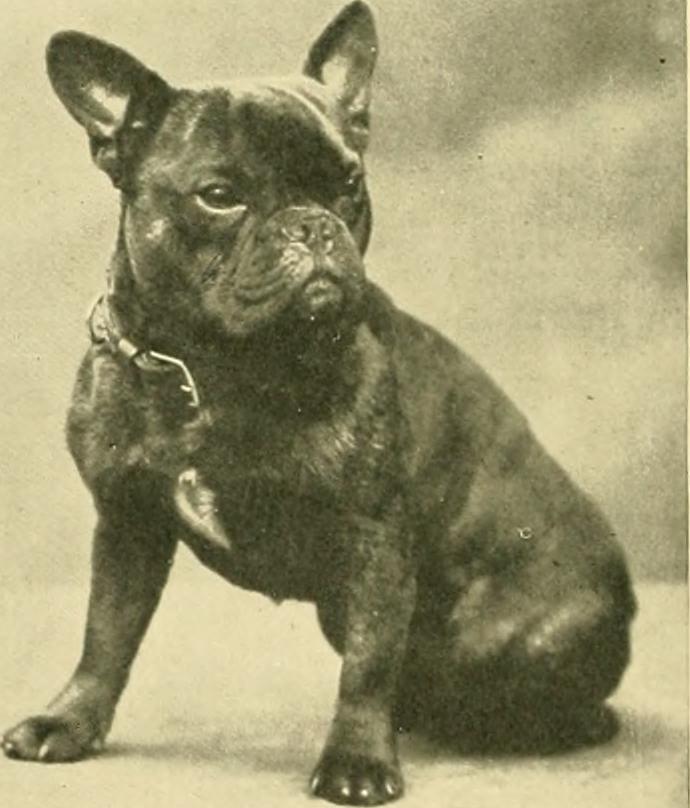

The 1800 Cynographia Britannica featured a detailed physical description of the bulldog, highlighting its distinctive round head, short nose, small ears, and sturdy build. Despite their popularity, purebred bulldogs faced a decline after bull baiting was banned in England in 1802. This led to some bulldogs being crossed with terriers to create stronger fighting dogs. As a result, crossbreeding between bulldogs and other breeds became more common during this era.

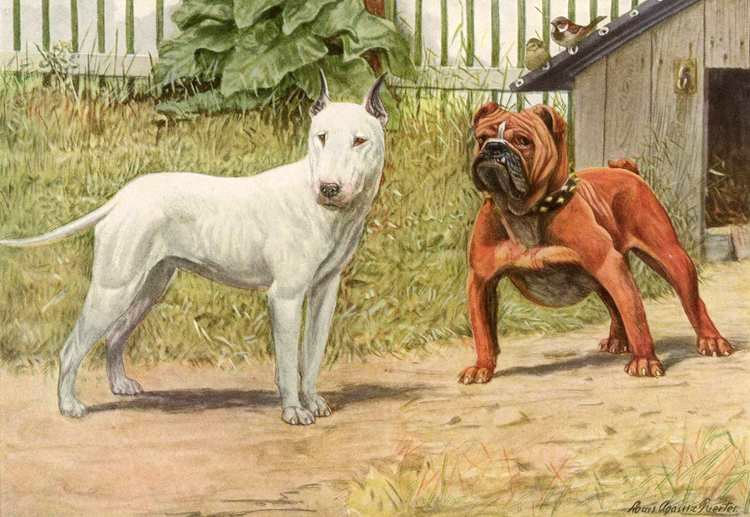

In 1919, a bull terrier was illustrated alongside an English bulldog, both breeds now facing health issues. A study from 2016 in Canine Genetics and Epidemiology delved into the limited genetic diversity of bulldogs, revealing their mastiff roots and possible crossbreeding with pugs. These findings shed light on the alterations to the skull and facial structure of present-day bulldogs, possibly due to selective breeding practices during the Victorian Era.

In the 1800s, during Queen Victoria’s reign, there was a surge in the popularity of breeding dogs to create specific, often quirky-looking breeds. This trend was fueled by the rise of dog contests, where breeders could showcase their unique creations. According to Veeramah, most of the breeds we know today can be traced back to this Victorian era of intense breeding. The active manipulation of dogs’ appearances during this time also led to significant changes in their genetics. David Sargan, a geneticist at Cambridge University, points out that each breed’s foundation had a lasting impact on the overall gene pool of dogs.